INDIA

Indian Physiography

India’s physiography, or its physical geography, is the result of complex geological and geomorphological processes that have shaped the country over millions of years. India’s unique landforms are the product of both endogenic forces (internal processes like tectonic movements) and exogenic forces (external processes like weathering and erosion). These processes have created diverse relief features that include towering mountain ranges, expansive plains, rugged plateaus, and intricate coastal regions.

Geological Evolution of India

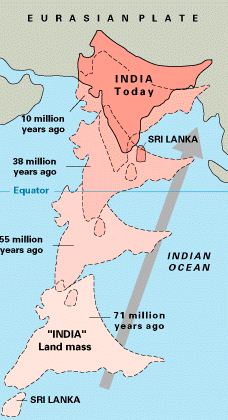

India’s geological history can be traced back to the break-up of the supercontinent Pangea around 225 million years ago. The Indo-Australian Plate, to which India belongs, began its northward drift, eventually colliding with the Eurasian Plate. This event led to the upliftment of the Himalayas, which still continue to rise today.

-

Formation of the Himalayas:

- The Himalayas were formed by the collision of the Indo-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate approximately 40-50 million years ago. This tectonic collision led to the compression and uplift of the sediments deposited in the ancient Tethys Sea, forming the Himalayan mountain range, one of the youngest and highest mountain systems in the world.

-

Formation of the Peninsular Plateau:

- The Peninsular Plateau, one of the most ancient landmasses on Earth, predates the Himalayan uplift. It forms part of the Gondwana land, which existed during the Precambrian era (around 2500 million years ago). This plateau is primarily composed of igneous and metamorphic rocks, and its stability is attributed to its location on a tectonically stable craton.

-

Formation of the Northern Plains:

- The Great Northern Plains of India were formed by the deposition of alluvium brought down by the rivers originating from the Himalayas. This deposition process began around 25 million years ago, following the upliftment of the Himalayas, when rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, and Indus started depositing sediments over the ancient bedrock.

-

Coastal Plains and Islands:

- The Coastal Plains of India, both on the eastern and western sides, have developed over time due to the action of sea waves, ocean currents, and riverine deposits. The formation of islands like the Andaman and Nicobar Islands is attributed to the tectonic activity at the juncture of the Indian Plate and the Burmese microplate, while the Lakshadweep Islands are primarily of coral origin.

Major Physiographic Divisions of India

India’s physiography can be classified into five distinct regions, each having unique geomorphological characteristics. These divisions are crucial in understanding India’s geography from both a natural and human perspective.

1. The Northern and North-Eastern Mountains

-

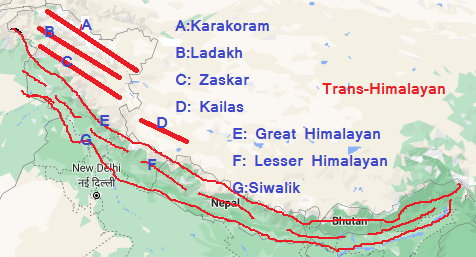

Himalayas: The northernmost part of India is occupied by the Himalayan mountain ranges. These ranges are classified into three parallel belts:

- The Greater Himalayas (Himadri): The highest range, housing peaks like Mount Everest and Kangchenjunga. It is primarily made of granite and hosts glaciers that feed the major river systems of the region.

- The Lesser Himalayas (Himachal): Situated south of the Greater Himalayas, this range is primarily made of metamorphic rocks. Famous hill stations like Shimla, Darjeeling, and Nainital are located in this range.

- The Outer Himalayas (Shivaliks): These are the youngest foothills of the Himalayas and are composed of unconsolidated sediments, making them highly prone to erosion and landslides.

-

Purvanchal Hills: These hills are an extension of the Himalayas in the northeastern states of India, including Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura. The ranges are not as tall as the Himalayas but play a significant role in the topography and drainage of the region.

2. The Great Northern Plains

- The Great Northern Plains stretch across northern India, extending from the Punjab Plains in the west to the Brahmaputra Valley in the east. Formed by the alluvial deposits of rivers like the Ganga, Indus, and Brahmaputra, this region is highly fertile and densely populated. It is divided into several subregions:

- Bhabar: A narrow belt of coarse sediments at the foothills of the Himalayas.

- Terai: A marshy region south of the Bhabar, known for its dense forests and wildlife.

- Bhangar and Khadar: The older and newer alluvial plains, respectively. The Khadar regions, with fresh deposits, are more fertile compared to the Bhangar.

3. The Peninsular Plateau

- The Peninsular Plateau is the oldest and most stable landmass in India. It comprises two major sub-regions:

- The Central Highlands: Located north of the Narmada River, these include the Malwa Plateau, Bundelkhand Plateau, and the Chota Nagpur Plateau. These regions are rich in mineral resources.

- The Deccan Plateau: South of the Narmada River, the Deccan Plateau extends to the southern tip of India. It is made of basaltic lava flows and is bounded by the Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats.

4. The Coastal Plains

- The Eastern Coastal Plains and the Western Coastal Plains are narrow strips of land located along the eastern and western edges of the Indian Peninsula, respectively.

- Western Coastal Plains: These are narrower and more rugged, extending from Gujarat to Kerala. They are divided into the Konkan Coast, Kanara Coast, and the Malabar Coast.

- Eastern Coastal Plains: These are broader and more fertile, extending from West Bengal to Tamil Nadu. Rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery form extensive deltas along these plains.

5. The Islands

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Located in the Bay of Bengal, these islands are a part of a submerged mountain range that runs parallel to the Arakan Yoma in Myanmar. These islands are of volcanic origin, and Barren Island in this group is the only active volcano in South Asia.

- Lakshadweep Islands: Situated in the Arabian Sea, these islands are of coral origin and have a distinct ecosystem with atolls and lagoons.

Timeline of India’s Geological Evolution

| Era | Event | Period (Million Years Ago) |

|---|---|---|

| Precambrian Era | Formation of the Peninsular Plateau | 2500-540 |

| Mesozoic Era | Break-up of Pangea; India begins northward drift | 225 |

| Cenozoic Era (Paleogene) | Indo-Australian Plate collides with Eurasian Plate | 50 |

| Cenozoic Era (Neogene) | Formation and uplift of the Himalayas | 40-50 |

| Quaternary Period | Alluvial deposition forms the Great Northern Plains | 25 |

Mains Questions

-

Discuss the geological evolution of India, highlighting the role of plate tectonics in the formation of the Himalayas and the Peninsular Plateau.

-

The Great Northern Plains of India are among the most fertile regions in the world. Analyze the factors contributing to their formation and fertility.

-

Explain the significance of the Peninsular Plateau in the Indian subcontinent, focusing on its geological structure and economic resources.

-

Compare and contrast the physiographic features of the Western Coastal Plains and the Eastern Coastal Plains. Discuss their significance in terms of agriculture, economy, and ecology.

The Northern Mountain Range: Trans Himalayas

The Northern Mountain Range of India, specifically the Trans-Himalayas, is a critical part of India’s physiography. These mountain ranges have been shaped over millions of years by the complex interaction between tectonic forces and geomorphological processes.

The Trans-Himalayan ranges, lying north of the Greater Himalayas, are vital both in terms of their geological significance and their strategic importance. The uplift of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau is a direct consequence of the Indian Plate’s collision with the Eurasian Plate, a process that is still active today.

Plate Tectonics and the Formation of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau

The Himalayas, one of the youngest and tallest mountain ranges in the world, are the result of the northward movement of the Indian Plate at a velocity of about 5 cm/year. This movement began around 225 million years ago, when the supercontinent Pangea broke apart, and the Indian Plate separated from Gondwana and started moving northward. The Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate about 40-50 million years ago, leading to the formation of the Himalayas.

Geological Process of Himalaya Formation

The region between the Indian and Eurasian plates was once occupied by the Tethys Sea. As the Indian Plate moved northward, the Tethys Ocean floor began to subduct beneath the Eurasian Plate. However, because both plates were continental, there was no significant density difference, and thus, the subduction was not straightforward. Instead, a continent-continent collision occurred, leading to the folding and crumbling of sediments deposited in the Tethys Sea. This process not only formed the Himalayas but also led to the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau.

The unique “double-layering effect” caused by the compression between two continental plates resulted in the thickening of the Earth’s crust in this region, which explains the enormous height of both the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau. The Himalayas are still rising, as the tectonic collision between the Indian and Eurasian Plates continues.

The uplift of the Himalayas occurred in three successive phases:

- Initial Phase: Formation of the Greater Himalayas.

- Second Phase: Formation of the Lesser Himalayas.

- Final Phase: Formation of the Shivaliks or Outer Himalayas.

The Trans-Himalayan Mountain Range

The Trans-Himalayas, also known as the Tibetan Himalayas, are located to the north of the Great Himalaya range and serve as a buffer between the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan Plateau. These ranges include several prominent subranges, each with its own geological and geographical significance.

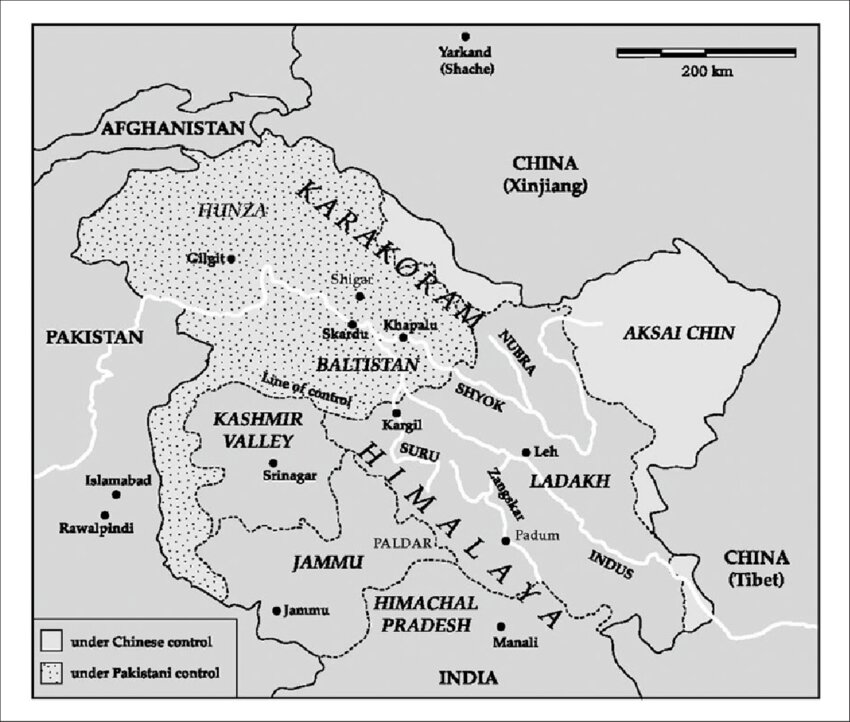

1. Karakoram Range

- Location: The Karakoram Range forms the northernmost range of the Trans-Himalayas.

- Geographical Significance: Known as the “backbone of high Asia,” the Karakoram is home to some of the world’s highest peaks, including K2 (the second-highest peak in the world). It serves as a watershed between the Indus River system in the south and the Tarim River system (Yarkand River) in the north.

- Glaciation: The Siachen Glacier, the world’s second-longest glacier outside the polar regions, is situated here, making the Karakoram a significant region for studying glacial dynamics.

2. Ladakh Range

- Location: South of the Karakoram Range, the Ladakh Range runs parallel to the Indus River.

- Geographical Significance: The Indus River cuts through the Ladakh Range, creating the deepest gorge in the Trans-Himalayas at Bunji.

- Cultural Significance: The Ladakh region has a rich Buddhist heritage, and its unique high-altitude landscape has made it a destination for trekking and adventure tourism.

3. Zanskar Range

- Location: To the south of the Ladakh Range, the Zanskar Range forms another prominent part of the Trans-Himalayas.

- Geographical Significance: The Zanskar Range forms a natural barrier, separating the Ladakh region from the rest of Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir. The region is known for its trekking routes, including the Chadar Trek along the frozen Zanskar River.

4. Kailash Range

- Location: The Kailash Range lies to the southeast of the Ladakh Range.

- Geographical Significance: It is home to Mount Kailash, one of the holiest peaks in the world, revered by Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Bon followers. Lake Mansarovar, located nearby, is also a significant religious site.

Fault Lines and Thrusts in the Himalayas

The Himalayan region is characterized by three prominent geological fault lines, which separate the different physiographic divisions of the mountain ranges. These faults are a result of the continuous tectonic forces at work in the region.

- Main Central Thrust (MCT): This fault line separates the Greater Himalayas from the Lesser Himalayas.

- Main Boundary Thrust (MBT): This fault separates the Lesser Himalayas from the Shivalik Range.

- Main Frontal Thrust (MFT): This marks the transition between the Shivalik foothills and the Indo-Gangetic Plains.

Timeline of Himalayan Formation

| Event | Period (Million Years Ago) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Break-up of Pangea | ~225 | Indian Plate begins northward drift |

| Subduction of Tethys Sea floor | ~200 | Formation of sediments that later become part of the Himalayas |

| Collision of Indian & Eurasian Plate | ~40-50 | Upliftment of the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau |

| Formation of Greater Himalayas | ~25-40 | Initial phase of Himalayan uplift |

| Formation of Lesser Himalayas | ~15-25 | Second phase of folding and uplift |

| Formation of Shivaliks | ~1-10 | Final phase of folding and uplift; formation of outer foothills |

Mains Questions

-

Examine the role of plate tectonics in the formation of the Trans-Himalayan region. How does the geological history of this region impact its present-day physiography?

-

Discuss the significance of the major fault lines in the Himalayas, including the Main Central Thrust, Main Boundary Thrust, and Main Frontal Thrust. How do they contribute to seismic activity in the region?

-

Analyze the importance of the Karakoram Range for India from a geographical and strategic perspective. What are the implications of its glacial systems on water security in South Asia?

-

The Trans-Himalayas are one of the least studied mountain ranges in the world. What are the potential research areas in this region, especially concerning climate change, glaciology, and biodiversity?

India’s Physiography: Himalayan Mountain Range (Great, Lesser, Outer Himalayas & North-East Mountains)

Regional Division of Himalayas: Kashmir Himalayas, Himachal & Uttarakhand Himalayas, Darjeeling & Sikkim Himalayas, Arunachal Himalayas

Important Mountain Passes

Mountain passes have played a crucial role in shaping history by facilitating trade, migration, and military operations. These natural corridors through mountain ranges have connected civilizations, cultures, and economies for millennia. In India, several key passes traverse the rugged Himalayan terrain, offering not only strategic military routes but also vital trade links between India and its neighbors.

Formation of Mountain Passes

Mountain passes are typically formed through a combination of natural processes, including:

- Glacial Erosion: Glaciers carve out valleys, which later become mountain passes.

- Fluvial Erosion: Rivers and streams erode mountain ridges, creating gaps or passes.

- Tectonic Activity: The shifting of Earth’s tectonic plates raises mountain ranges, but certain areas remain lower, forming natural passes.

Physiographically, a mountain pass is a low point or gap between peaks in a mountain range. Many passes have a saddle-shaped structure, and often serve as routes between valleys. Their significance is immense, from easing human migration to shaping the political and economic landscape of regions.

Historical Significance of Passes in India

Mountain passes in India have been pivotal in the following ways:

- Trade Routes: Passes have enabled historical trade routes, such as the Silk Route, allowing goods, culture, and ideas to flow between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

- Military Campaigns: Strategic passes like Zoji La and Khardung La have been crucial in defense strategies, particularly during conflicts in the northern region of India.

- Cultural Exchange: Passes have been gateways to cultural exchanges, including the spread of Buddhism from India to Tibet and beyond.

Key Mountain Passes in India (Geographic Distribution)

1. Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh Region

- Aghil Pass (Karakoram Range): Important for military strategies, located near the disputed India-China border.

- Karakoram Pass (Karakoram Range): Part of the ancient Silk Route, connecting Ladakh to Central Asia.

- Burzil Pass (Great Himalayan Range): Connects Srinagar to Gilgit; historically used for trade between India and Central Asia.

- Banihal Pass (Pir Panjal Range): Vital for connecting Jammu with Kashmir Valley; the Jawahar Tunnel and NH44 pass through it.

- Zoji La (Zanskar Range): NH1 passes through this, linking Srinagar to Leh, important for defense and trade.

- Khardung La (Ladakh Range): One of the highest motorable passes, connecting Leh with the Nubra and Shyok valleys, critical for defense.

- Chang La (Ladakh Range): Connects Leh with Pangong Lake.

2. Himachal Pradesh

- Baralacha La (Zanskar Range): Connects Lahaul-Spiti with Ladakh, key for the Manali-Leh highway.

- Shipki La (Great Himalayas): The Satluj River enters India through this pass, and it connects India with Tibet.

- Rohtang Pass (Pir Panjal Range): Connects Kullu Valley with Lahaul-Spiti; the Atal Tunnel beneath it provides all-year access, making it critical for both tourism and strategic military movement.

3. Uttarakhand

- Mana Pass (Great Himalayas): Gateway to Tibet, and a route for pilgrimages to Mansarovar and Mount Kailash.

- Niti Pass (Great Himalayas): Close to the Mana Pass, another key route towards Tibet.

- Lipulekh Pass (Great Himalayas): Located at the tri-junction of India, Tibet, and Nepal, this pass is used for the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra and holds strategic significance.

4. Sikkim

- Nathu La (Great Himalayas): A trade route between India and China, also used for the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra.

- Jelep La (Great Himalayas): Another key trade route between Sikkim and Tibet.

5. Northeast India

- Bomdi La (Arunachal Pradesh): Connects India with Tibet and is an important route for the northeastern states.

- Diphu Pass (Arunachal Pradesh): Located at the tri-junction of India, China, and Myanmar.

- Lekhapani Pass (Assam): Key for military movement and trade.

- Tuju Pass (Manipur): Provides connectivity between India and the ASEAN region.

Timeline of Mountain Passes in Indian History

| Period | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient (2000 BCE) | Formation of the Silk Route through passes like Karakoram | Enabled trade and cultural exchange between Asia |

| Medieval (12th Century) | Zoji La and Banihal used by Mughal armies | Expanded Mughal influence in Kashmir and Ladakh |

| British Era (19th Century) | British expeditions through Nathu La and Burzil Pass | Opened up new trade routes and solidified British control |

| Post-Independence (1947) | Military use of Khardung La, Zoji La during Indo-Pak wars | Crucial for India’s defense and border management |

| Modern Era (21st Century) | Development of Atal Tunnel at Rohtang Pass | Strategic connectivity to Lahaul-Spiti and beyond |

Detailed Physiographic Features

- Khardung La (Ladakh Range): Known as one of the highest motorable roads in the world at 5,359 meters. It serves a strategic role in connecting Leh to the northern valleys and is key for military logistics.

- Baralacha La (Zanskar Range): Situated at an altitude of 4,890 meters, this pass connects the Lahaul valley with Ladakh, offering a scenic but rugged route for adventure tourism.

- Lipulekh Pass (Great Himalayas): At an elevation of 5,200 meters, this pass has been a traditional route for pilgrimages to Kailash Mansarovar, symbolizing its religious importance along with strategic concerns due to its proximity to China and Nepal.

Mains Questions

- Discuss the strategic importance of mountain passes in India, with reference to military operations and trade. (250 words)

- Examine how mountain passes have historically influenced India’s cultural and religious exchanges with Central Asia. (150 words)

- Explain the role of modern infrastructure development, such as the Atal Tunnel, in enhancing the accessibility of remote regions through mountain passes. (200 words)